<!-- .slide: data-state="title" -->

# Documentation

===

<!-- .slide: data-state="standard" -->

<img style="height: 550px;" src="./media/documentation/paint.png"/>

===

<!-- .slide: data-state="standard" -->

## Examples of documentation

+ Think of projects with good documentation.

_What do you like about them?_

+ Think of projects with less good documentation.

_What don't you like about them? Are you missing anything?_

<quotation>NB: You can choose a mature library with lots of users, but try to also think of less mature projects you had to collaborate on, or papers you had to reproduce.</quotation>

===

<!-- .slide: data-state="standard" -->

## Types of documentation

<div class="fragment">

+ README files and CITATION files

+ In-code documentation (Docstrings)

+ API documentation

+ Tutorials

+ ...

</div>

===

<!-- .slide: data-state="standard" -->

## A good README file

+ README file is first thing a user/collaborator sees

+ What should be included in README files?

<ul>

<li contenteditable="true">...</li>

<li contenteditable="true">...</li>

<li contenteditable="true">...</li>

<li contenteditable="true">...</li>

<li contenteditable="true">...</li>

<li contenteditable="true">...</li>

<li contenteditable="true">...</li>

</ul>

Note:

+ A descriptive project title

+ Motivation (why the project exists) and basics

+ Installation / How to setup

+ Copy-pasteable quick start code example

+ Usage reference (if not elsewhere)

+ Citation if someone uses it

+ Other related tools ("see also")

+ Contact information for the developer(s)

+ Badges

+ License information

+ Contributing guidelines

===

<!-- .slide: data-state="standard" -->

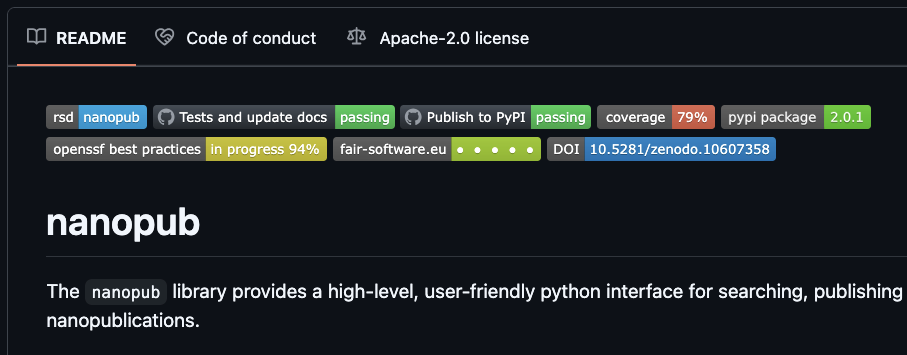

## Badges

Badges are a way to quickly show the status of a project: is it building, is it tested, what is the license?

You typically find them on top of the README file.

.

===

<!-- .slide: data-state="standard" -->

## Why citation?

+ Unlike papers, softwares are difficult to cite

+ To get credit, provide citation information at the root of your project, e.g. using a CITATION.cff (Citation File Format) file.

+ Citation files are easy to create (e.g. using cffinit)

+ Gather all the required information in one place

+ Automatically picked up by platforms like GitHub, Zenodo ...

===

<!-- .slide: data-state="standard" -->

## Minimal example of CITATION.cff file

```yaml

authors:

- family-names: Doe

given-names: Jane

cff-version: 1.2.0

message: "If you use this software, please cite it using the metadata from this file."

title: "My research software"

```

===

<!-- .slide: data-state="standard" -->

## Why write in-code documentation?

In-code documentation:

+ Makes code more understandable

+ Explains decisions we made

===

<!-- .slide: data-state="standard" -->

## When **not** to use in-code documentation?

+ When the code is self-explanatory

+ To replace good variable/function names

+ To replace version control

+ To keep old (zombie) code around

===

<!-- .slide: data-state="standard" -->

## Readable code vs commented code

```python=

# convert from degrees celsius to fahrenheit

def convert(d):

return d * 5 / 9 + 32

```

vs

```python=

def celsius_to_fahrenheit(degrees):

return degrees * 5 / 9 + 32

```

===

<!-- .slide: data-state="standard" -->

## What makes a good comment?

**Comment A**

<pre data-id="code-animation"><code style="overflow: hidden;" data-trim class="python">

# Now we check if temperature is larger than -50:

if temperature > -50:

print('do something')

</code></pre>

**Comment B**

<pre data-id="code-animation"><code style="overflow: hidden;" data-trim class="python">

# We regard temperatures below -50 degrees as measurement errors

if temperature > -50:

print('do something')

</code></pre>

How are these different? Which one do you prefer?

===

<!-- .slide: data-state="standard" -->

## Docstrings: a special kind of comment

```python=

def celsius_to_fahrenheit(degrees):

"""Convert degrees Celsius to degrees Fahrenheit."""

return degrees * 5 / 9 + 32

```

Why is this OK?

Note:

Docstrings can be used to generate user documentation.

They are accessible outside the code.

They follow a standardized syntax.

===

<!-- .slide: data-state="standard" -->

## In-code commenting: key points

+ Explicit, descriptive naming already provides important documentation.

+ Comments should describe the why for your code, not the what.

+ Writing docstrings is an easy way to write documentation while you code, as they are accessible outside the code itself.

===

<!-- .slide: data-state="standard" -->

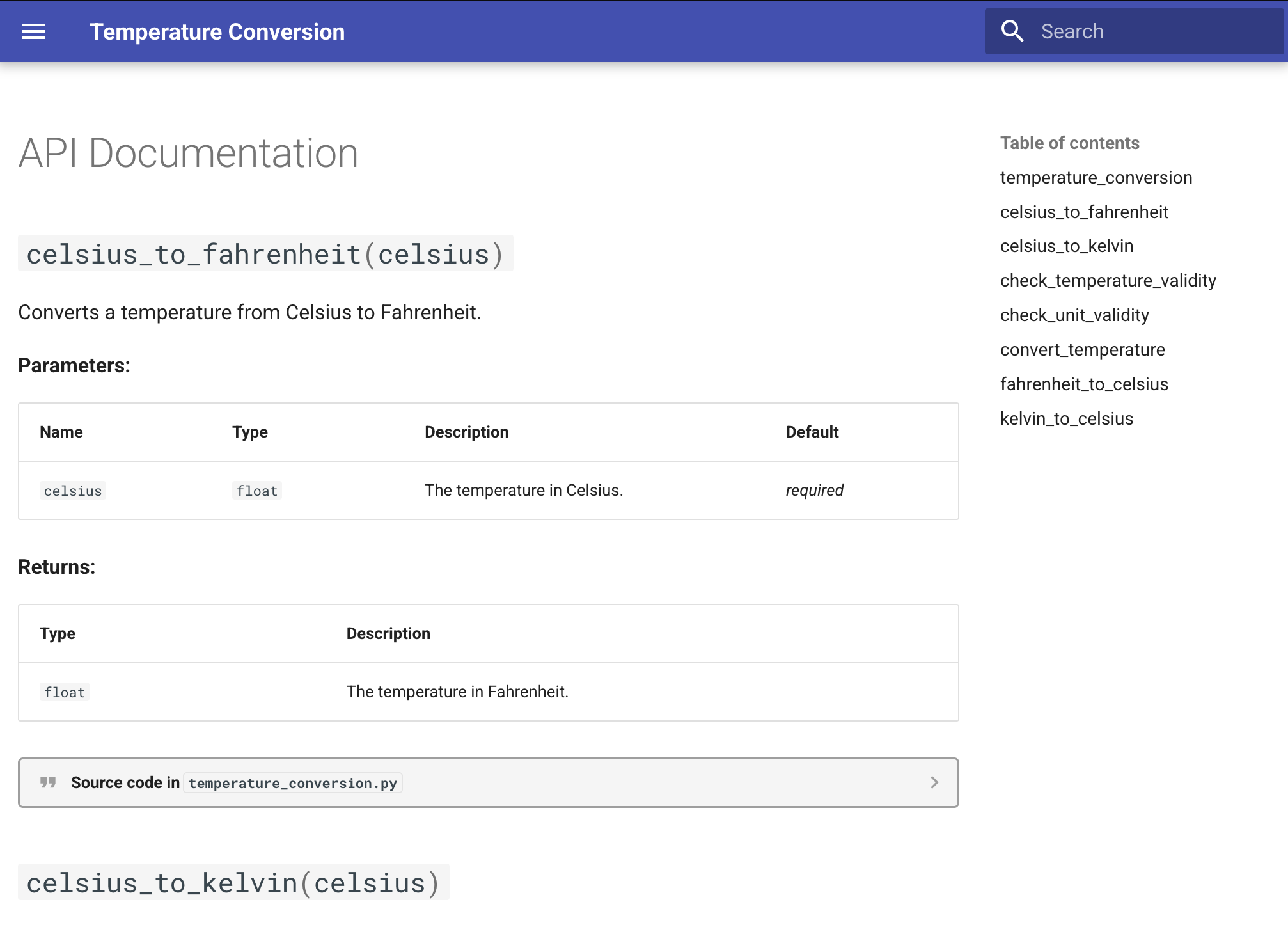

## User/API documentation

+ What if a README file is not enough?

+ How do I easily create user documentation?

===

<!-- .slide: data-state="standard" -->

## Tools

+ Documentation generators (e.g. **mkdocs**, **Sphinx**)

- creates nicely-formatted HTML pages out of .md or .rst files

- numerous plugins available to extend functionality (API, spellcheck, etc.)

- programming language independent

- easy to use and deploy (e.g. GitHub pages)

- **mkdocs** easier to start with, but **Sphinx** is more complete and robust

+ **Github pages** (deploy your documentation)

- set up inside your GitHub repository

- automatically deploys your Sphinx-generated documentation

===

<!-- .slide: data-state="standard" -->

## Using **mkdocs**

+ In a new code directory, run `mkdocs new .`

+ Edit the `mkdocs.yml` file to configure your documentation

+ Run `mkdocs build` to generate the documentation site

+ Run `mkdocs serve` to serve the documentation site (open in your browser)

+ Use the `mkdocstrings` to automatically generate API documentation

+ Use `mkdocs gh-deploy` to deploy your documentation to GitHub

===

<!-- .slide: data-state="standard" -->

## Using **mkdocs**

===

<!-- .slide: data-state="standard" -->

## Take-home message

+ Depending on the purpose and state of the project documentation needs to meet different criteria.

+ Documentation can take different shapes:

+ Readable code

+ In-code comments

+ Docstrings

+ README files

+ Tutorials/notebooks

+ Documentation is a vital part of a project, and should be kept and created alongside the corresponding code.