Medical Imaging Modalities

Last updated on 2024-08-14 | Edit this page

Estimated time: 50 minutes

Overview

Questions

- What are the common different types of diagnostic imaging?

- What sorts of computational challenges do they present?

Objectives

- Explain various common types of medical images

- Explain at a high level how images’ metadata is created and organized

Introduction

Medical imaging uses many technologies including X-rays, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound, positron emission tomography (PET) and microscopy. Although there are tendencies to use certain technologies, or modalities to answer certain clinical questions, many modalities may provide information of interest in terms of research questions. In order to work with digital images at scale we need to use information technology. We receive images in certain types of files, e.g., an x-ray stored at the hospital in DICOM format, but the image itself is contained in a JPEG inside the DICOM as a 2D-array. Understanding all the kinds of files we are dealing with and how the images within them were generated can help us deal with them computationally.

Conceptually, we can think of medical images as signals. These signals need various kinds of processing before they are ‘readable’ by humans or by many of the algorithms we write.

While thinking about how the information from these signals is stored in different file types may seem less exciting than what the “true information” or final diagnosis from the image was, it is necessary to understand this to make the best algorithms possible. For example, a lot of hospital images are essentially JPEGs. This has implications in terms of image quality as we manipulate and resize the images.

The details of various forms of imaging will be covered in a lecture with slides that accompanies this episode. Below are a few summaries about various ultra-common imaging types. Keep in mind that manufacturers may have specificities in terms of file types not covered here, and there are many possibilities in terms of how images could potentially be stored. Here we will discuss what is common to get in terms of files given to researchers.

X-Rays

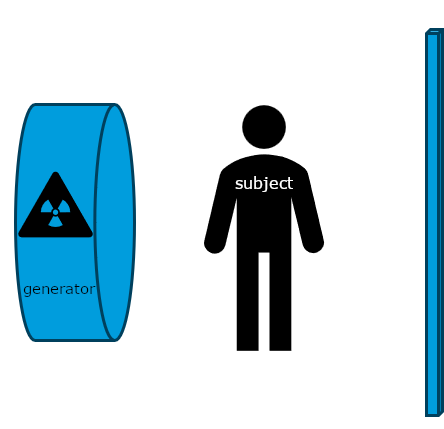

Historically, x-rays were the first common form of medical imaging. The diagram below should help you visualize how they are produced. The signal from an x-ray generator crosses the subject. Some tissues attenuate the radiation more than others. The signal is captured by an x-ray detector (you can think of this metaphorically like photographic film) on the other side of the subject.

Modern x-rays are born digital. No actual “film” is produced, rather a DICOM file which contains arrays in JPEG files. Technically, the arrays could have been (and sometimes even are) put in PNG or other types of files, but typically JPEGs are the ones used for x-rays. We could use the metaphor of a wrapped present here. The DICOM file contains metadata around the image data, wrapping it. The image data itself is a bunch of 2D-arrays, but these have been organized to a specific shape - they are “boxed” by JPEG files. JPEG is a container format. There are JPEG files (emphasis on the plural) because almost no x-ray can be interpreted clinically without multiple perspectives. In chest-x-rays implies a anteroposterior and a lateral view. We can take x-rays from any angle and even do them repeatedly, and this allows for flouroscopy. Flouroscopy images are stored in a DICOM but can be displayed as movies because they are typically cine-files. Cine- is a file format that lets you store images in sequence with a frame rate.

Computed Tomography and Tomosynthesis

There are several kinds of tomography. This technique produces 3D-images, made of voxels, that allow us to see structures within a subject. CTs are extremely common, and helpful for many diagnostic questions, but have certain costs in terms of not only time and money, but also radiation to patients.

CTs and tomosynthetic images are produced with the same technology. The difference is that in a CT the image is based on a 360 degree capture of the signal. You can conceptualize this as a spinning donut with the generator and receptor opposite to each other. Tomosynthesis uses a limited angle instead of going all the way around the patient. In both cases, the image output is then made by processing this into a 3D-array. We see again, similarly to x-ray, what tissues attenuated the radiation, and what tissues let it pass, but we can visualize it in either 3D or single layer “slices” of voxels. It is not uncommon to get CTs as DICOM CT projection data (DICOM-CT-PD) files which can then be processed before viewing, or in some cases stored off as other file types.

Ultrasounds

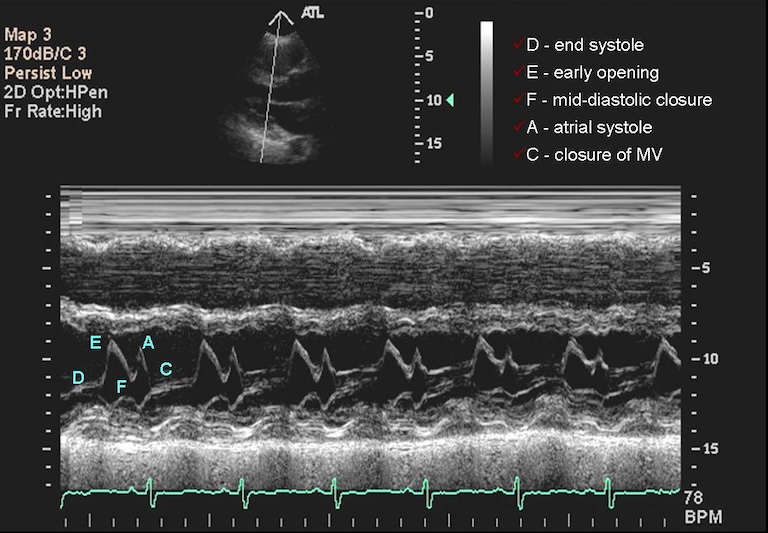

Ultrasounds can produce multiple complex types of images. Typically, sonographers produce a lot of B-mode images. They use high frequency sound waves, sent and captured from a piezoelectric probe (also known as a transducer) to get 2D-images. Just as different tissues attenuate radiation differently, different tissues attenuate these waves differently, and this can help us create images after some processing of the signal. These images can be captured in rapid succession over time, so they can be saved as cine-files inside DICOMs. On the other hand, the sonographer can choose to record only a single ‘frame’, in which case a 2D-array will ultimately be saved. B-mode is far from the only type of ultrasounds. M-mode, like the cine-files in B-mode, can also capture motion, but puts it into a a single 2D-array of one line of the image over time. In the compound image below you can see a B-mode 2D-image and an M-mode made on the line in it.

What Are Some Disadvantages to Ultrasounds in Terms of Computational Analysis?

Ultrasounds images are operator-dependent, often with embedded patient data, and the settings and patients’ positions can vary widely.

Challenge: How to Reduce These Problems?

How can we optimize research involving ultrasounds in terms of the challenges above?

Possible solutions include:

- Reviewing metadata on existing images so it can be matched by machine type

- Training technicians to use standardized settings only

- Creating a machine set only on one power setting

- Image harmonization/normalization algorithms

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRIs are images made by utilizing some fairly complicated physics in terms of what we can do to protons (abundant in human tissue) with magnets and radiofrequency waves, and how we capture their signal. Different ordering and timing of radiofrequency pulses and different magnetic gradients give us different MRI sequences. The actual signal on an anatomical MRI needs to be processed via Fourier transforms and some other computational work before it is recognizable as anatomy. The raw data is reffered to as the k-space data, and this can be kept in vendor specific formats or open common formats, e.g., ISMRMRD (International Society of Magnetic Resonance MR Raw Data). In practice, we rarely use the k-space data (unless perhaps we are medical physicists) for research on medical pathology. The final product we are used to looking at is a post-processed 3D-array wrapped inside a DICOM file. We can transform the image, and parts of the metadata, to a variety of file types commonly used in neuroscience research. These file types will be covered in more detail later in the course.

Other Image Types

PET scans, nuclear medicine images in general and pathology images are also broadly available inside hospitals. Pathology is currently undergoing a revolution of digitalization, and a typical file format has not emerged yet. Pathology images may be DICOM, but could also be stored as specific kinds of TIFF files or other file types. Beyond the more common types of imaging, researchers are actively looking into new forms of imaging. Some add new information to old modalities, like contrast-enhanced ultrasounds. Other new forms of imaging are novel in terms of the signal, such as terahertz imaging, which uses a previously ‘unused’ part of the electomagnetic radiation spectrum. As you might guess, the more novel the imaging, usually the less consolidation there is around file types and how they are organized. It is useful to remember that all these file types, whether on established image types or novel ones, are sorts of ‘containers’ for the ‘payload’ of the actual images which are the arrays. Often we simply need to know how to get the payload array out of its container and/or where to find certain metadata.

Image Storage

There is less standardization around file formats of certain types of imaging.

For example, while typical radiological images have settled in how they are recorded in DICOM, more novel sequences, such as arterial spin-labeled ones, do not have a standardized way of how they are recorded in it. As mentioned above, pathology images are not neccesarily stored in DICOM, and there is some controversy as to what file format will dominate this important form of medical imaging.

Key Points

- Each imaging modality provides distinct sets of information

- In computational imaging, images are essentially arrays, although embedded in additional data structures

- Research should be thoughtfully designed, taking into account the constraints and capabilities inherent in human capacities

- We can expect the emergence of additional imaging modalities in the future