Preprocessing numerical features#

Note: The content in this notebook combines

02_numerical_pipeline_hands_on.pyand02_numerical_pipeline_scaling.pyfrom the original materials.

In the previous notebook, we trained a k-nearest neighbors model on some data. However, we oversimplified the procedure by loading a dataset that contained exclusively numerical data. Besides, we used datasets which were already split into train-test sets.

In this notebook, we aim at:

using a scikit-learn helper to separate data into train-test sets;

training and evaluating a more complex scikit-learn model;

an example of preprocessing: identifying, selecting and scaling numerical variables;

using a scikit-learn pipeline to chain preprocessing and model training.

We start by loading the adult census dataset used during the data exploration.

Loading the entire dataset#

As in the previous notebook, we rely on pandas to open the CSV file into a pandas dataframe.

import pandas as pd

adult_census = pd.read_csv("../datasets/adult-census.csv")

# drop the duplicated column `"education-num"` as stated in the first notebook

adult_census = adult_census.drop(columns="education-num")

# Separate target from the data

data, target = adult_census.drop(columns="class"), adult_census["class"]

Note

Here and later, we use the name data and target to be explicit. In

scikit-learn documentation, data is commonly named X and target is

commonly called y.

At this point, we can focus on the data we want to use to train our predictive model.

Identify numerical data#

Numerical data are represented with numbers. They are linked to measurable (quantitative) data, such as age or the number of hours a person works a week.

Predictive models are natively designed to work with numerical data. Moreover, numerical data usually requires very little work before getting started with training.

The first task here is to identify numerical data in our dataset.

Caution

Numerical data are represented with numbers, but numbers do not always represent numerical data. Categories could already be encoded with numbers and we may need to identify these features.

Using a few variables to represent the general idea, let’s look at the data types of these variables:

data[["age", "hours-per-week", "sex", "race"]].dtypes

age int64

hours-per-week int64

sex object

race object

dtype: object

The two types are integer int64 and object. We can look at the first few lines

of the dataframe to understand the meaning of the object data type.

data[["age", "hours-per-week", "sex", "race"]].head()

| age | hours-per-week | sex | race | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 25 | 40 | Male | Black |

| 1 | 38 | 50 | Male | White |

| 2 | 28 | 40 | Male | White |

| 3 | 44 | 40 | Male | Black |

| 4 | 18 | 30 | Female | White |

We see that the object data type corresponds to columns containing strings.

As we saw in the exploration section, these columns contain categories and we

will see later how to handle those. We can select the columns containing

integers and check their content.

numerical_columns = ["age", "capital-gain", "capital-loss", "hours-per-week"]

data[numerical_columns].head()

| age | capital-gain | capital-loss | hours-per-week | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 40 |

| 1 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 50 |

| 2 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 40 |

| 3 | 44 | 7688 | 0 | 40 |

| 4 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 30 |

We store the subset of numerical columns in a new dataframe.

data_numeric = data[numerical_columns]

Train-test split the dataset#

In the previous notebook, we loaded data from two separate datasets: a training one and

a testing one.

A better way is to do this automatically. In scikit-learn, we can use the helper function

sklearn.model_selection.train_test_split to

split the dataset into two subsets.

Later, we will see that this is useful when building bigger pipelines with sklearn.

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

data_train, data_test, target_train, target_test = train_test_split(

data_numeric, target, random_state=42, test_size=0.25

)

Tip

In scikit-learn setting the random_state parameter allows to get

deterministic results when we use a random number generator. In the

train_test_split case the randomness comes from shuffling the data, which

decides how the dataset is split into a train and a test set).

Here, we assigned 25% of the sampels to the testing set (which is also the default) and 75% of the samples

to the training set.

Model fitting without preprocessing#

Instead of the k-nearest neighbors model, we use a logistic regression model. This belongs to the family of linear models, and is more widely used than the k-nearest neighbors model.

Note

To recap, linear models find a set of weights to combine features linearly and predict the target. For instance, the model can come up with a rule such as:

if

0.1 * age + 3.3 * hours-per-week - 15.1 > 0, predicthigh-incomeotherwise predict

low-income

To create a logistic regression model in scikit-learn we can do:

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

model = LogisticRegression()

Now that the model has been created, we can use it exactly the same way as we

used the k-nearest neighbors model previously. In particular, we

can use the fit method to train the model using the training data and

labels:

model.fit(data_train, target_train)

LogisticRegression()In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook.

On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

LogisticRegression()

We can also use the score method to check the model generalization

performance on the test set.

accuracy = model.score(data_test, target_test)

print(f"Accuracy of logistic regression: {accuracy:.3f}")

Accuracy of logistic regression: 0.807

Model fitting with preprocessing#

A range of preprocessing algorithms in scikit-learn allow us to transform the input data before training a model. In our case, we will standardize the data and then train a new logistic regression model on that new version of the dataset.

Let’s start by printing some statistics about the training data.

data_train.describe()

| age | capital-gain | capital-loss | hours-per-week | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | 36631.000000 | 36631.000000 | 36631.000000 | 36631.000000 |

| mean | 38.642352 | 1087.077721 | 89.665311 | 40.431247 |

| std | 13.725748 | 7522.692939 | 407.110175 | 12.423952 |

| min | 17.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 1.000000 |

| 25% | 28.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 40.000000 |

| 50% | 37.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 40.000000 |

| 75% | 48.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 45.000000 |

| max | 90.000000 | 99999.000000 | 4356.000000 | 99.000000 |

We see that the dataset’s features span across different ranges. Some algorithms make some assumptions regarding the feature distributions and normalizing features is usually helpful to address such assumptions.

Tip

Here are some reasons for scaling features:

Models that rely on the distance between a pair of samples, for instance k-nearest neighbors, should be trained on normalized features to make each feature contribute approximately equally to the distance computations.

Many models such as logistic regression use a numerical solver (based on gradient descent) to find their optimal parameters. This solver converges faster when the features are scaled, as it requires less steps (called iterations) to reach the optimal solution.

Whether or not a machine learning model requires scaling the features depends on the model family. Linear models such as logistic regression generally benefit from scaling the features while other models such as decision trees do not need such preprocessing (but would not suffer from it).

We show how to apply such normalization using a scikit-learn transformer

called StandardScaler. This transformer shifts and scales each feature

individually so that they all have a 0-mean and a unit standard deviation.

We recall that transformers are estimators that have a transform method.

We now investigate different steps used in scikit-learn to achieve such a transformation of the data.

First, one needs to call the method fit in order to learn the scaling from

the data.

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

scaler = StandardScaler()

scaler.fit(data_train)

StandardScaler()In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook.

On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

StandardScaler()

The fit method for transformers is similar to the fit method for

predictors. The main difference is that the former has a single argument (the

data matrix), whereas the latter has two arguments (the data matrix and the

target).

In this case, the algorithm needs to compute the mean and standard deviation for each feature and store them into some NumPy arrays. Here, these statistics are the model states.

Note

The fact that the model states of this scaler are arrays of means and standard

deviations is specific to the StandardScaler. Other scikit-learn

transformers may compute different statistics and store them as model states,

in a similar fashion.

We can inspect the computed means and standard deviations.

scaler.mean_

array([ 38.64235211, 1087.07772106, 89.6653108 , 40.43124676])

scaler.scale_

array([ 13.72556083, 7522.59025606, 407.10461772, 12.42378265])

Note

scikit-learn convention: if an attribute is learned from the data, its name

ends with an underscore (i.e. _), as in mean_ and scale_ for the

StandardScaler.

Scaling the data is applied to each feature individually (i.e. each column in the data matrix). For each feature, we subtract its mean and divide by its standard deviation.

Once we have called the fit method, we can perform data transformation by

calling the method transform.

data_train_scaled = scaler.transform(data_train)

data_train_scaled

array([[ 0.17177061, -0.14450843, 5.71188483, -2.28845333],

[ 0.02605707, -0.14450843, -0.22025127, -0.27618374],

[-0.33822677, -0.14450843, -0.22025127, 0.77019645],

...,

[-0.77536738, -0.14450843, -0.22025127, -0.03471139],

[ 0.53605445, -0.14450843, -0.22025127, -0.03471139],

[ 1.48319243, -0.14450843, -0.22025127, -2.69090725]])

Let’s illustrate the internal mechanism of the transform method and put it

to perspective with what we already saw with predictors.

The transform method for transformers is similar to the predict method for

predictors. It uses a predefined function, called a transformation

function, and uses the model states and the input data. However, instead of

outputting predictions, the job of the transform method is to output a

transformed version of the input data.

Finally, the method fit_transform is a shorthand method to call successively

fit and then transform.

In scikit-learn jargon, a transformer is defined as an estimator (an

object with a fit method) supporting transform or fit_transform.

data_train_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(data_train)

data_train_scaled

array([[ 0.17177061, -0.14450843, 5.71188483, -2.28845333],

[ 0.02605707, -0.14450843, -0.22025127, -0.27618374],

[-0.33822677, -0.14450843, -0.22025127, 0.77019645],

...,

[-0.77536738, -0.14450843, -0.22025127, -0.03471139],

[ 0.53605445, -0.14450843, -0.22025127, -0.03471139],

[ 1.48319243, -0.14450843, -0.22025127, -2.69090725]])

By default, all scikit-learn transformers output NumPy arrays. Since

scikit-learn 1.2, it is possible to set the output to be a pandas dataframe,

which makes data exploration easier as it preserves the column names. The

method set_output controls this behaviour. Please refer to this example

from the scikit-learn

documentation

for more options to configure the output of transformers.

scaler = StandardScaler().set_output(transform="pandas")

data_train_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(data_train)

data_train_scaled.describe()

| age | capital-gain | capital-loss | hours-per-week | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| count | 3.663100e+04 | 3.663100e+04 | 3.663100e+04 | 3.663100e+04 |

| mean | -2.273364e-16 | 3.530310e-17 | 3.840667e-17 | 1.844684e-16 |

| std | 1.000014e+00 | 1.000014e+00 | 1.000014e+00 | 1.000014e+00 |

| min | -1.576792e+00 | -1.445084e-01 | -2.202513e-01 | -3.173852e+00 |

| 25% | -7.753674e-01 | -1.445084e-01 | -2.202513e-01 | -3.471139e-02 |

| 50% | -1.196565e-01 | -1.445084e-01 | -2.202513e-01 | -3.471139e-02 |

| 75% | 6.817680e-01 | -1.445084e-01 | -2.202513e-01 | 3.677425e-01 |

| max | 3.741752e+00 | 1.314865e+01 | 1.047970e+01 | 4.714245e+00 |

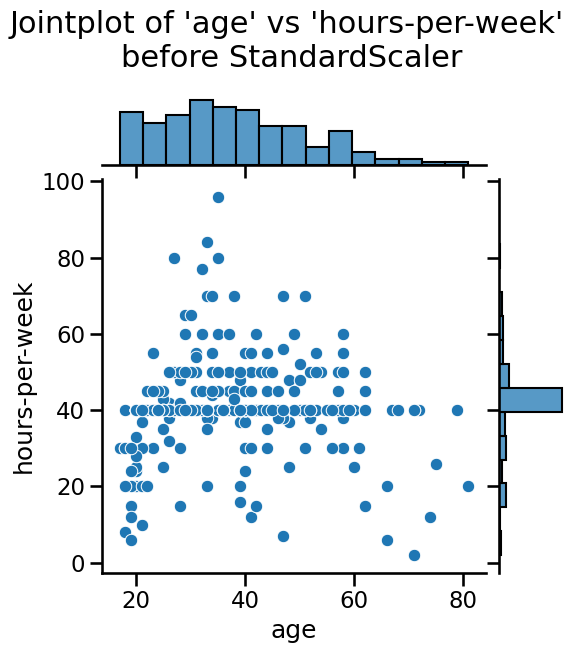

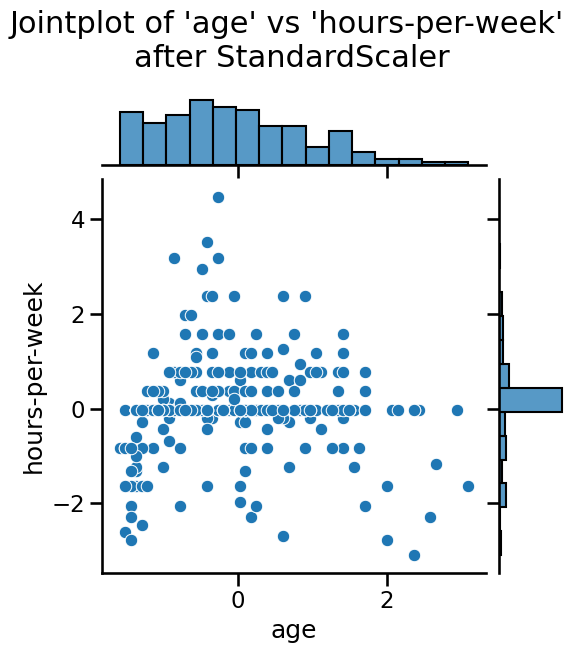

Notice that the mean of all the columns is close to 0 and the standard

deviation in all cases is close to 1. We can also visualize the effect of

StandardScaler using a jointplot to show both the histograms of the

distributions and a scatterplot of any pair of numerical features at the same

time. We can observe that StandardScaler does not change the structure of

the data itself but the axes get shifted and scaled.

Note to instructor: We strongly advise to copy-paste below code and discuss the visualization with your audience. We discourage using live-coding here, because you will spend a lot of time fiddling with the jointplot, time which we can better use to introduce machine learning.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

# number of points to visualize to have a clearer plot

num_points_to_plot = 300

sns.jointplot(

data=data_train[:num_points_to_plot],

x="age",

y="hours-per-week",

marginal_kws=dict(bins=15),

)

plt.suptitle(

"Jointplot of 'age' vs 'hours-per-week' \nbefore StandardScaler", y=1.1

)

sns.jointplot(

data=data_train_scaled[:num_points_to_plot],

x="age",

y="hours-per-week",

marginal_kws=dict(bins=15),

)

_ = plt.suptitle(

"Jointplot of 'age' vs 'hours-per-week' \nafter StandardScaler", y=1.1

)

We can easily combine sequential operations with a scikit-learn Pipeline,

which chains together operations and is used as any other classifier or

regressor. The helper function make_pipeline creates a Pipeline: it

takes as arguments the successive transformations to perform, followed by the

classifier or regressor model.

import time

from sklearn.linear_model import LogisticRegression

from sklearn.pipeline import make_pipeline

model = make_pipeline(StandardScaler(), LogisticRegression())

model

Pipeline(steps=[('standardscaler', StandardScaler()),

('logisticregression', LogisticRegression())])In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook. On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

Pipeline(steps=[('standardscaler', StandardScaler()),

('logisticregression', LogisticRegression())])StandardScaler()

LogisticRegression()

The make_pipeline function did not require us to give a name to each step.

Indeed, it was automatically assigned based on the name of the classes

provided; a StandardScaler step is named "standardscaler" in the resulting

pipeline. We can check the name of each steps of our model:

model.named_steps

{'standardscaler': StandardScaler(),

'logisticregression': LogisticRegression()}

This predictive pipeline exposes the same methods as the final predictor:

fit and predict (and additionally predict_proba, decision_function, or

score).

model.fit(data_train, target_train)

Pipeline(steps=[('standardscaler', StandardScaler()),

('logisticregression', LogisticRegression())])In a Jupyter environment, please rerun this cell to show the HTML representation or trust the notebook. On GitHub, the HTML representation is unable to render, please try loading this page with nbviewer.org.

Pipeline(steps=[('standardscaler', StandardScaler()),

('logisticregression', LogisticRegression())])StandardScaler()

LogisticRegression()

We can represent the internal mechanism of a pipeline when calling fit by

the following diagram:

When calling model.fit, the method fit_transform from each underlying

transformer (here a single transformer) in the pipeline is called to:

learn their internal model states

transform the training data. Finally, the preprocessed data are provided to train the predictor.

To predict the targets given a test set, one uses the predict method.

predicted_target = model.predict(data_test)

predicted_target[:5]

array([' <=50K', ' <=50K', ' >50K', ' <=50K', ' <=50K'], dtype=object)

Let’s show the underlying mechanism:

The method transform of each transformer (here a single transformer) is

called to preprocess the data. Note that there is no need to call the fit

method for these transformers because we are using the internal model states

computed when calling model.fit. The preprocessed data is then provided to

the predictor that outputs the predicted target by calling its method

predict.

As a shorthand, we can check the score of the full predictive pipeline calling

the method model.score. Thus, let’s check the

generalization performance of such a predictive pipeline.

model_name = model.__class__.__name__

score = model.score(data_test, target_test)

print(f"The accuracy using a {model_name} is {score:.3f} ")

The accuracy using a Pipeline is 0.807

We can compare the pipeline using scaling and logistic regression with using a logistic regression model without scaling like we did before. We will not go into how to do this comparison with Python in sake of time, instead we directly give the results:

The accuracy using a Pipeline is 0.807 with a fitting time of 0.043 seconds in 9 iterations The accuracy using a LogisticRegression is 0.807 with a fitting time of 0.110 seconds in 60 iterations

We see that scaling the data before training the logistic regression was beneficial in terms of computational performance. Indeed, the number of iterations decreased as well as the training time. The generalization performance did not change since both models converged.

Warning

Working with non-scaled data will potentially force the algorithm to iterate

more as we showed in the example above. There is also the catastrophic

scenario where the number of required iterations is larger than the maximum

number of iterations allowed by the predictor (controlled by the max_iter)

parameter. Therefore, before increasing max_iter, make sure that the data

are well scaled.

Notebook recap#

In scikit-learn, the score method of a classification model returns the

accuracy, i.e. the fraction of correctly classified samples. In this case,

around 8 / 10 of the times the logistic regression predicts the right income

of a person. Now the real question is: is this generalization performance

relevant of a good predictive model? Find out by solving the next exercise!

In this notebook, we learned:

to use a scikit-learn helper to separate data into train-test sets;

to train and evaluate a more complex scikit-learn model;

about preprocessing for numerical variables;

to use a scikit-learn pipeline to chain preprocessing and model training.