Introduction to model coupling

Last updated on 2022-10-31 | Edit this page

Overview

Questions

- What is meant by a “model”?

- What is the difference between a mathematical model and a computational model?

- What is model coupling?

- Why would we want to couple simulation models?

Objectives

- Explain the benefits of coupling simulation models

Introduction

Computer simulations are widely used in modern science to understand and predict the behaviour of natural systems. The computer program that simulates a given physical system is referred to as a model of that system. For example, a climate simulation code is a model of the Earth’s climate. Some models may be very simple e.g. describing the evolution of a 1 dimensional system. Others may be highly complex, involving many different physical processes. A well known use of computer simulation is in the field of weather forecasting, in which a very complex model composed of a multitude of different physical processes must be simulated by a computer program, generally requiring powerful supercomputers.

Mathematical model vs computational model

For this course, it is important to distinguish between a mathematical model, and a computational model. A mathematical model refers to the set of mathematical equations that describe the evolution of a given physical system. The computational model refers to the actual computer program that describes the evolution of a physical system. These are closely connected concepts - after all, many computational models are just solving a given mathematical model numerically. However, the distinction is important. Some computational models can be simulating many different aspects of a physical system, which could involve solving many different mathematical models. The process of making sure that a computational model is solving the mathematical model you think it is, is called verification.

What is model coupling?

In short, “coupling” one computational model to another means that we pass information between the models in order to connect them into one big model. If the output of one model can be used as the input of another, for example, then it may be possible to couple them. The models must of course be compatible - at least one model must calculate something that can be used by the other model.

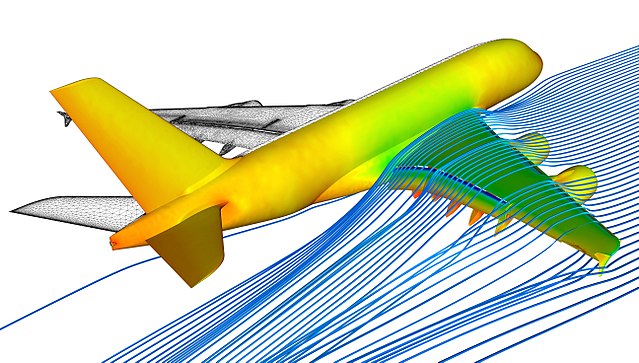

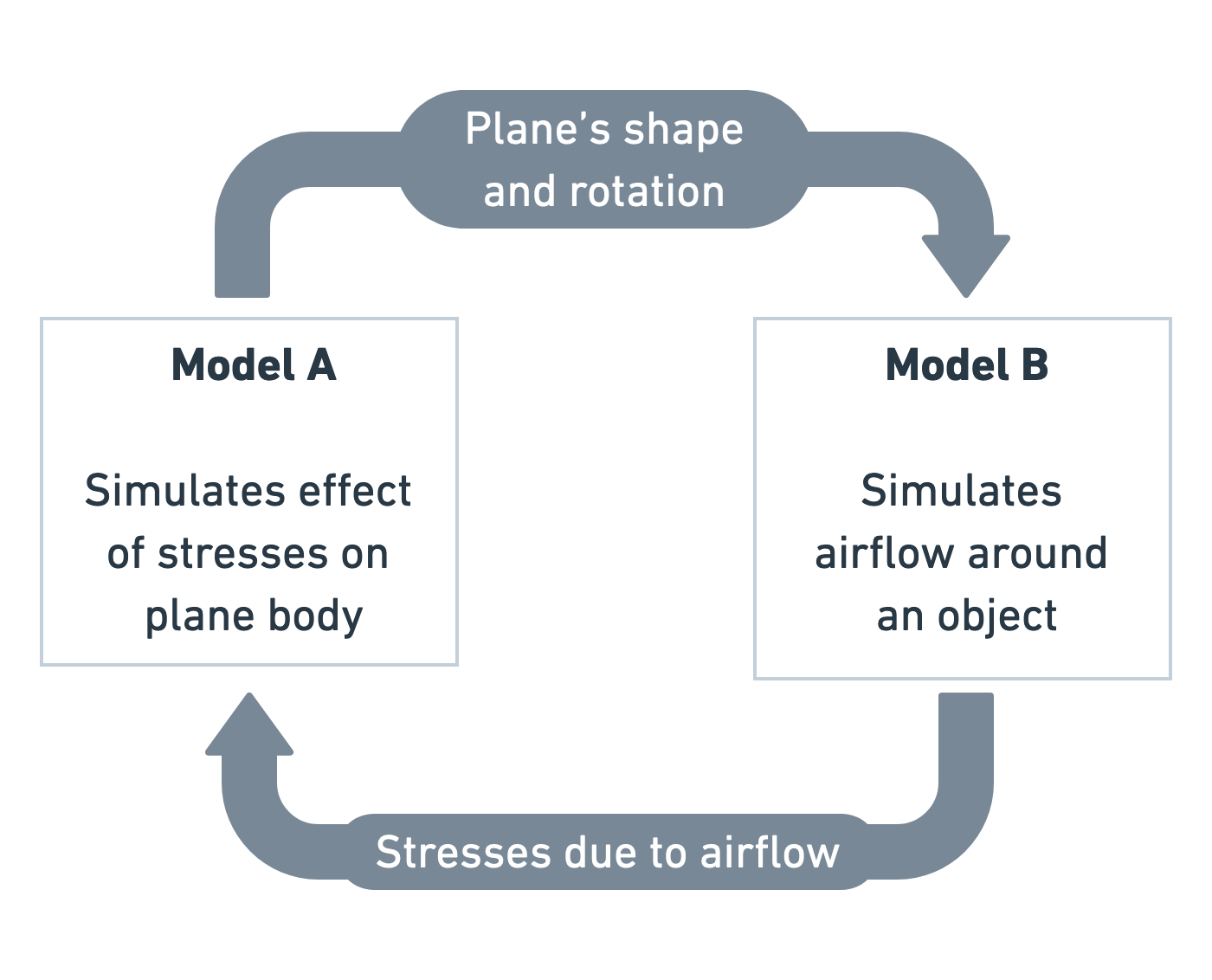

An example: Making a coupled model of a flying aeroplane

Imagine that we wish to simulate a flying aeroplane, but we only have two separate models: Model A and Model B.

Model A simulates how an aeroplane moves in response to forces on its body. Model B simulates airflow around objects and calculates the forces generated by that airflow. We could pass the shape, speed and rotation of the airplane as input to Model B, allowing it to calculate the forces on the plane. In turn, we could then pass the calculated forces back to Model A, allowing it to calculate the effect of the forces on the plane’s speed, position and rotation. In this way we have coupled the two models together, making a new, more complex computational model. The two original models are submodels of the coupled model.

Exercise: Breaking it down

Think of another system you might want to simulate. Can you think of how to break it down into two or more computational submodels? Most importantly, consider what information would be passed from one model to the other.

- Local climate-ecology: One model simulates the expected climate of a region of the Earth under certain vegetation/land use conditions. A separate model simulates the proliferation and behaviour of animals and vegetation in a given region under influence of various climatic conditions.

- Stent in a blood vessel: There is a computational fluid dynamics model (simulating the blood flow) through a stent. A separate model is modelling the growth of scar tissue, that covers the stent as the artery wall heals. The stresses created by the blood on the stent and tissue affect how it grows. In turn, the new, narrowed arterial wall needs to be passed back to the blood flow model, since new tissue will affect the flow.

Why couple models together?

It is generally simpler and cheaper to simulate a small part of a system, or specific physical interaction. Processes at different length or time scales are often subject to different forces, while they can neglect others. For example, a mechanical model of a car frame will not consider behaviour at the atomic scale, whereas a molecular dynamics simulation naturally must. Computational modelling is therefore often highly specialised.

Furthermore, there can be an enormous number of different computational models even for the same problem, at the same length and time scales. Some models may be more accurate than others, or include newer theory etc. A scientist or engineer will combine different submodels together to run different computational experiments.

Why bother? Let’s just have one big model

Rather than couple existing models together, it is of course possible to simply create a single, monolithic model that handles all of the interactions within it. Can you think of reasons why we would not want to do that?

- Code re-use: If a model already exists then ideally you should reuse it, rather than re-invent the wheel.

- Separation of concerns: The submodel does ‘one thing and does it well’ (hopefully). The modularity of keeping code separate in this way can really help with long term maintenance of a large comple simulation model. This is particularly obvious when models simulate processes that happen on totally different and non-overlapping length and time scales.

- Speed of building new models: If people can construct a complex model out of smaller, highly tested and optimised building blocks, then the task is a lot less laborious.

- Ease of swapping new, different models in and out. If a new, faster or more accurate implementation of a model is released, you want to be able to swap out an existing submodel for it. Having everything in a single monolithic code can lead to a tangled mess that is harder to refactor. In many cases it will just not be worth the time to refactor the existing simulation code, and people will write a new one, or not try the new model at all.

- Performance: A model coupling approach often makes it easier to exploit the massive parallelism of supercomputers.

Key Points

- Crossing the scales

- Modularity

- Flexibility

- Performance